Sometimes people get crazy ideas. This happens to all of us. Something strikes us and we decide, against all sanity to the contrary, that it needs doing or we need a particular something. In gaming for example, a console gamer seeing an unfamiliar video game with an interesting box and back text says to himself “Let’s give it a try, looks pretty cool!” Once it’s home and the playing commences the sinking feelings begin at the first sign of bad graphics or poor game play. No later than five minutes into it he realizes the reason why he hadn’t heard of this particular title before. Buying game that without any inkling of what was in that box is bonafide insanity.

If I consider the above description to define a gamers disease, then there is a pox upon me. And a nasty one at that.

Way back in 1979 board and roleplaying games were taking off big. The hobby game industry was exploding and many wanted in on the action. One of these was a printing company that woke up one  morning and decided who better to get in on making board games than a printing company? Yaquinto printing went out and hired a couple of experienced game designers and set out to create the next generation of board games. One of these games in their initial run was The Beastlord.

morning and decided who better to get in on making board games than a printing company? Yaquinto printing went out and hired a couple of experienced game designers and set out to create the next generation of board games. One of these games in their initial run was The Beastlord.

If I recall correctly we saw the description for Beastlord in a gaming magazine or an insert in one of the other Yaquinto titles. It sounded really impressive: fight as Elves, Human, or monsters in a struggle to control a fertile valley. Build your civilization up and vie for dominance. It had tons of counters representing everything from archers to livestock. It even had strategic and tactical maps! This could be the fantasy wargame we had been looking for for so long. (Which really wasn’t that long but he when you’re a kid six months feels like an eternity.)

We scrimped together enough to order a copy and waited patiently (back then you waited patiently for everything.) We bided our time anticipating its arrival with visions of sacked cities and burning fields. When it arrived we descended on it like the plague of locusts (surely they must be simulated in the game as well!), punching counters and reading rules, gazing at the map and pondering strategies.

So right about now in my tale of game desires gone wrong, you are expecting the horrible realization to dawn on us that Beastlord wasn’t what we expected. The truth is we never really settled on whether the game met our expectations or not. The beastlord himself never really got the opportunity to do much pillaging. Nowhere was a field burning, not even a stalk of wheat. Each time we set out to play the game we were interrupted and never finished a complete game. According to the back of the box play time ranged between one and three hours. For the games we started we felt that this was perhaps overly optimisitc. When you added setup time to this it really required a block of several contiguous hours and for reasons multifarious, we never seemed to get that block.

Then one evening the question of completing a game was settled for us. As the box lay on the gaming table for a night long session (we were fond of playing until the sun came up, and at that youthful age we could do it too), disaster struck. An accidental nudge and the box went catapulting onto the floor. The six-hundred die cut counters, cozily arranged in their nice compartments, flew forth and turned into a multi-colored pile. We stood in shock. With silent reverence, my friend used the box top to scrape the counters into the box, replaced the book and maps, and closed it. As it turned out, forever. We never resorted the counters, and over time our Beastlord copy was lost to us but not forgotten.

Fast Forward to present day. That old friend (who you will be hearing more about), is returning to South Florida, and here is where the insanity begins. Naturally we’ve been plotting and planning which board games to put in queue for play. Old favorites like GDW’s Double Star, and SPI’s The Conquerors were discussed, and then with the gleam of insanity in overzealous eyes we shout a chorus of “The Beastlord!”

It was fairly easy to find a copy of the game and not only that an unpunched mint copy as well. And on the cheap which I am sure underscores the games popularity. At some point this fall or winter we will be sitting down to a session of The Beastlord and this time we mean to finish it. If we accomplish this feat (given our sordid history with this game you never know for certain), I will provide BattlePlay’s readers with a full review of the game in all of its pillaging and field burning glory. Hopefully, after all of this, it actually turns out to be worth it.

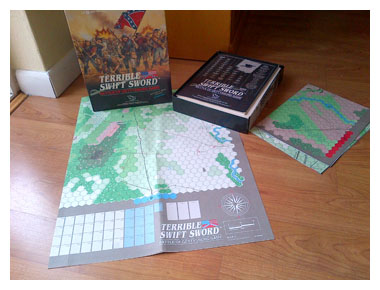

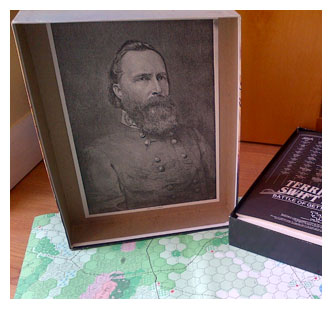

in an honored place on my game shelf was a gift by one of my oldest friends. Together we spent countless hours in our youth playing the classic war games, from the venerable Tactics II to contemporary games like Ultimatum. The year 1986 was at the twilight of classical board war gaming and this copy of Terrible Swift Sword was the last boxed war game either of us purchased. That in itself gives it an emotional edge, being the last of its kind; but what made this even more special is that it was bought in Gettysburg. We were both Civil War buffs and his trip to Gettysburg while on leave with the U.S. army was one of those seminal moments for any student of the conflict. I knew he would be visiting the battlefield (by a written letter to me, yes handwritten; this was 1986 and email was unheard of), but when he came back with a copy of a game we had read about but never had seen a copy of (remember no internet either), well, I was ecstatic. At this point in our lives things were changing, I was in college, he had his military career, and the time we had to sit down to a lengthy board game was hard to come by. That scarcity of opportunity made the few times we were able to play even more special.

in an honored place on my game shelf was a gift by one of my oldest friends. Together we spent countless hours in our youth playing the classic war games, from the venerable Tactics II to contemporary games like Ultimatum. The year 1986 was at the twilight of classical board war gaming and this copy of Terrible Swift Sword was the last boxed war game either of us purchased. That in itself gives it an emotional edge, being the last of its kind; but what made this even more special is that it was bought in Gettysburg. We were both Civil War buffs and his trip to Gettysburg while on leave with the U.S. army was one of those seminal moments for any student of the conflict. I knew he would be visiting the battlefield (by a written letter to me, yes handwritten; this was 1986 and email was unheard of), but when he came back with a copy of a game we had read about but never had seen a copy of (remember no internet either), well, I was ecstatic. At this point in our lives things were changing, I was in college, he had his military career, and the time we had to sit down to a lengthy board game was hard to come by. That scarcity of opportunity made the few times we were able to play even more special.  Being students of the battle, we often discussed General

Being students of the battle, we often discussed General